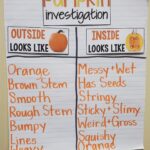

Among other things happening in the Beluga classroom this week, we have been exploring interesting adjectives. Autumn naturally lends itself to adjectives because there are so many things about it which appeal to our senses –the sight of the brilliant colors of leaves and grasses, the damp, earthy, and slightly sour smells of the woods this time of year, feeling the crisp air on our skin, and hearing dry leaves crunch under our feet. Halloween-time also provides wonderful opportunities for expanding vocabulary because there are so many interesting and unusual things to be described! Why limit yourself to words such as “wet” and “gross” to describe the inside of a pumpkin, when you could use words like “squishy”, “stringy”, or “slimy”? Language acquisition has always fascinated me, and, as an early childhood teacher, I know that a child’s oral language skills are a strong predictor of their future reading skills. A rich language base, which is also tied to cognitive growth and experience, provides a strong foundation for reading, writing, and comprehension later on in school. Children who have large vocabularies and good knowledge of the alphabet learn to read more easily than do those without that background. Consequently, we focus a lot of attention on oral language skills in preschool.

- What is the outside of a pumpkin like?

- What words can we use to describe our pumpkin?

- What is the inside of a pumpkin like?

The first step in acquiring language is speech perception. Babies’ brains are uniquely designed to receive sounds and make meaning from them – their brains are wired for processing language. Studies have shown that infants have the ability to discern all of the phonemes which human mouths are able to produce. The tones and patterns and combinations of sounds may vary from language to language, but babies are able to recognize and distinguish between them all. Sometime between the ages of 6-12 months, however, babies’ brains begin to hone in on the phonemes of the particular language in which they are immersed, and their brains begin pruning out the phonemes which aren’t being used. Babies begin to specialize in not only the sounds of their native language but also the cadence and flow, pauses, and stresses which are unique to it. And, amazingly, if a child is immersed in two or more languages, the child’s brain is able to sort out all of these moving parts and become fluent in each of them as well.

Speech perception leads to the second stop in language acquisition: speech production. At about the age of 7-8 months, babies begin to coo and babble in the phonemes in which they have been immersed. This period is crucial because as they experiment and practice producing these sounds which they will use to form the words this will, this will allow them to begin communicating with their families. These words will be made up of sounds with a variety of pitches, tones, and stresses all combined in different patterns to form meaning in their particular language.

The acquisition of vocabulary is also an interesting part of language. How does the brain learn which combination of sounds constitutes words in any given language, and how is meaning assigned to these combinations? It seems easy enough to point to objects and name them, but how is meaning extrapolated from words which are not nouns? What about abstract ideas such as adjectives and other parts of speech, or even the things which exist only in the imagination? In other words, how do you describe the inside of a pumpkin?

Then there is also grammar – the system of rules which govern a language – to consider. It isn’t enough to make sounds into words – you must follow the rules of morphology and syntax of your particular language. To be understood, a person must be able to combine and re-combine these words into (limitless) sentences using a set of rules universally understood by people in their group. A couple of things enable a child to accomplish this task: entering the world with a brain already wired for language learning and having an intense interest in their caregivers and other people, who surround them. These people both model and teach grammar, whether correct or incorrect and often without even meaning to do so.

Because reading grows out of oral language, the foundation for reading is laid in a child’s life long before they can even speak. When caring adults engage in frequent active conversations with children and offer positive guidance and responses to them, children’s vocabularies and language skills grow quickly. These experiences begin with those little “conversations” adults have with children beginning in infancy, and which continue and expand every day of a child’s life. These conversations involve everyday topics, but ideally, they should also include lots of silly rhymes, poems, chants, jokes, and songs. Studies have shown that there is a direct correlation between academic achievement and the amount and quality of oral language a child is exposed to between the ages of birth and five years.

- Oh dear! How does our jack o’ lantern feel??

In our preschool classes, as we are providing meaningful learning experiences to students, we are also working diligently to build on the language foundation which caring family members have given already given their children so that they will have a rich language base as they enter Kindergarten, and be better prepared to become the exceptional learners we know they can be.